The community’s many losses and the distortion of their history is only now being acknowledged.

In these

ten years, a growing swell of voices have shown that the dominating images of

Partition – the trains filled with dead bodies and the women forced to jump into

wells to save the family “honour” – are only elements of the picture.

There are

many factors which make the Sindh story different. Originally a Hindu and then

Buddhist land – as was the rest of India – Islam came to Sindh as early as CE

711. It grew steadily and peacefully with Sufi values of tolerance, integration.

Fluid belief systems dominated all forms of worship. This ecosystem endures

among Sindhis even today, in locations around the world.

Through

centuries of paying tribute to Delhi and Kabul, indigenous prince of Sindh

ruled largely undisturbed. Non-Muslims migrated from neighbouring provinces

confident of a relatively non-discriminatory environment – Nankapanthis from

Punjab, and worshippers of various Hindu deities from other parts. Over time,

they evolved into a comfortable, prosperous minority with an eclectic belief

system.

|

| Hindu temple in Malaga, Spain, Saaz Aggarwal, 2013 |

One group

served in the courts of the princes, rising to positions of responsibility and

even power, and came to be known as the Amils of Sindh. The larger part of the

community were traders, from the omnipresent village grocer and moneylender to

those with a larger reach and empires that stretched inland all the way to

Russia, China and Japan and Iran on the other side.

The British

occupied Sindh in 1843 – in gross violation of treaties of eternal friendship

with the princes – their descriptions of the barbarism a transparent and rather

weak defence of the annexation. They also wrote of the sad plight of the

Hindus, but a closer look at indigenous accounts of the time reinforces the “comfortable,

prosperous minority” version.

The British

occupation was a setback to the traders of Sindh but they soon used the

opportunity to expand using the steamship routes and set up retail outlets in

ports around the world. In 1999, a French scholar, Claude Markovits,

published a detailed account of how this group of South Asian merchants had

carved a niche for themselves in a European-dominated world economy.

The Amils, meanwhile, had soon been recruited into

the British administration and switched quickly from Persian to English. Their

commitment to education led to increased opportunities. They began setting up

their own schools, and educated their daughters. The Dayaram Jethmal Sind

College – Dayaram

Jethmal Government Science College today

– one of the finest institutes of higher education in India at the time, was

built and funded by the Hindus of Sindh. By the early 20th century,

the Hindus were the backbone of the Sindh administration as well as its

economy.

All this while, Sindh had been a part of the

Bombay Province and in 1936, it was given provincial autonomy. The separation

was not made on communal lines but for more administrative care and focused

development. In fact it was a Hindu, Harchandrai Vishindas, who

first expressed this need at a Congress assembly in 1913.

|

| The DJ Sind Arts College in Karachi in 1893. Credit: Zainub via Flicker, Public domain. |

The Second World War was occupying the British

and so was the Indian freedom struggle. When Mohandas Gandhi demanded that the

British “Quit India!” the response around the country was tremendous, and no

less in Sindh. There are numerous examples, not least

being the sound system used by the Indian National Congress which was contributed

and personally monitored by Nanik Motwane of Chicago Radio, an electrical

business that started in Larkana, Sindh, and with head office in Bombay.

Men, women and children of Sindh participated in

the freedom movement, most poignant and heroic being the case of 19-year-old Hemu

Kalani. Arrested for his participation in Quit India, he was sentenced to

death. The response to mercy petitions was that he would be pardoned if he

revealed the names of his co-conspirators. Remembers Madhuri Sheth, 13 years

old at the time,

He was hanged at

midnight and we sat up in wait until the body was cremated behind the primary

school where I studied.

When the line of Partition was drawn, it was

believed that, well integrated as a religious minority for centuries, the

Hindus – about one-fourth of the population – would continue as such. And Sindh

was given in its entirety to Pakistan.

As Partition

approached, tension rose and reports of the massacres in other areas caused

fear and uncertainty. When an influx of migrants entered Sindh from other parts

of India, things began to change dramatically. Dr

Mohini Hingorani, 17 years old at the time, was a student at DJ Sind College,

Karachi. She remembers:

When the trouble started before

Partition, Bunder Road Extension where we lived remained unaffected. But Gadi

Khata, where the college was, had severe riots and some of my father’s

stepbrothers were caught in the crossfire. One of them was killed.

Still, the Sindhi

Partition story is marked by less violence than in any other area. Karachi

remained calm even in December 1947. Cases of abduction and even decapitation

were reported – but they were few. This changed with the January 6, 1948, pogrom.

Thirteen-year-old Khushi Khubchandani

stood on the terrace of his home and could see mobs carrying away radios,

furniture and valuables. If anyone resisted, they were attacked. People escaped

mobs who attacked buses by reciting verses from the Quran. A very large number

were saved by Muhajirs who put themselves in danger to protect them.

The exodus began,

with fleeing people crowding the docks to escape.

Some tried to stay

on. Pribhdas

Tolani, a once well-known landlord of Larkana, had no

intention of leaving. In October 1948, he was arrested and imprisoned in Sukkur

Jail, accused of being an Indian spy. His eldest son, Gopal Tolani, Sessions Judge

in Sukkur at the time, could do nothing but watch, in helplessness and despair.

When Pribhdas Tolani was released, it was on condition that he leave Pakistan

and never return. So it was not just mobs of the homeless and victimized who

wanted the Hindus of Sindh out so that they could claim their property – the

government too participated.

|

| Mansharam and Rukmani Wadhwani (Dr Mohini’s uncle and aunt) with three of their children, on the second floor of the family building in Sukkur. The beautiful Sadh Belo temple, accessed by boat, could be seen from this terrace which had cots on which they slept at night in summer. |

The newly truncated

India, economically depleted by centuries of colonial rule, further drained by

the Second World War, was hardly in a position to receive the lakhs of fleeing

refugees but did make a tremendous effort. Army camps around the country were rundown,

but had the infrastructure. The homeless ones were taken there in droves.

Remembered T.

Sushila Rao, wife of a camp commandant at Kalyan,

If I ever woke

before dawn and looked out, I would see a long line of the Sindhi refugees

walking to the station on their way to Bombay for the day to work or trade or

study. They had lost everything but did not weep and complain. How hardworking

they were!

Sindh had many

women doctors and teachers, even in the 1930s and 40s – but most middle-class women

did not go out to work. After Partition, women of many families contributed

economically. Some used domestic skills, making papad and pickles which their

menfolk sold from door to door; some took in sewing. Others went to work as

telephone operators, secretaries, assembly-line workers.

Many of these

refugees had lost not just their homes and their homeland but also their

comfortable lives and sources of livelihood. The Bombay Refugee Act of 1947 was

a further slap on the face with the restrictions it placed. The Sindhi

community fought back with indignation. By definition, a refugee is a stateless

person – and they were in their own country for whose independence they had

sacrificed so much! The Act was modified and a new definition, ‘displaced

persons’ was coined.

|

| Kaka Pribhdas Tolani (1893-1988) and his sons, Gopaldas, Pribhdas, Nandlal, Chandru, Bombay, c1970s. Having left Sindh with nothing, Kaka Tolani was one of the many Sindhi entrepreneurs who began by building a home for himself and his family, but continued in the ‘construction line’ and went on to build some of the best known-buildings in Bombay. He also built a number of colleges in Gandhidham which are still run by his family.

|

Yet another blow came when the constitution failed to list Sindhi as

an Indian language. Aghast, the writers and thinkers of the community recruited

the young Ram Jethmalani to lead their campaign and Sindhi was included in

Schedule VIII of the Indian constitution – but only in 1967. So while Sindhi

parents had stopped speaking to their children in their mother tongue in an

effort to acquire languages which would help them in their new lives, the state

played its own role in the extinction.

The biggest support

came from within the community, with doors being opened to members of extended

families, friends and business associates. And the wealthy ones were most

generous, contributing materially to the camps, providing employment within

their enterprises and campaigning relentlessly to the government for matters

such as hawking licenses and support in housing development.

There are a very

large number of names, too many to list here, but among the best known is Nanik

Motwane in Bombay for his extraordinary efforts on behalf of the “refugees” at

every level. Ramnarayan Chellaram in

Bangalore contributed with material relief and also helped the “refugees” protect

their rights as citizens preparing identity documentation, applications for

compensation, admissions to educational institutions and other requirements.

Certificate of domicile of Situ Kishinchand Bijlani, who was 13 years old at the time and lived 30 years as the wife of a planter in the Nilgiris – but preserved this precious document all her life

Sahijram Gidwani

lived in Ahmedabad: he had studied at Cambridge and was retained as tutor to

Vikram and Gautam Sarabhai through their secondary schooling and later headed

the Sarabhai Empire's Calico Mills, which contributed substantially to refugee

relief. As the numbers increased, he moved to Bombay and took up an honorary

position as chairman of the newly instituted Bombay Housing Board.

One of the most

interesting histories is of Bhai Pratap, one of the businessmen with a global

retail chain, who with Gandhi's help acquired a piece of land from the Maharao

of Kachchh to create a “new Sindh”. It was Bhai Pratap who initiated the

development of Kandla Port. He assured the Maharao that he would bring enough

business to Kandla so that it would soon match up to and exceed the volume of

trade done by Karachi. He was also instrumental in having Kandla designated as

a free-trade zone – Asia’s first – in 1965.

Meanwhile, the

refugee camps in Bombay, Poona, Ahmedabad, Ajmer, Bhopal, and other places grew

into hives of industry. Being homeless, the Sindhis built homes for themselves.

In time, they would change the skyline of these cities. From the camps rose

other tremendous institutions – factories, hospitals, educational institutions.

For a community that had lost its ancestral homeland forever, the names they

chose – Jai Hind, Jai

Bharat, National and so on – are poignant indeed.

Seventy-five

years later, the Sindhis are respected for their contributions and for the way

they have integrated. What is often not noticed is the magnificent way in which

this heterogenous community behaved as one: each

person, each family, each group felled by Partition simply stood up and kept

moving. Their contribution is seen and appreciated – but the loss of their

language, music, poetry, philosophy – and the distortion of their history – is only

now being acknowledged, as an important aspect of the story of the 1947

Partition of India.

Saaz Aggarwal is a biographer, oral historian and artist. See her website here.

We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.First appeared here on Aug 13, 2022

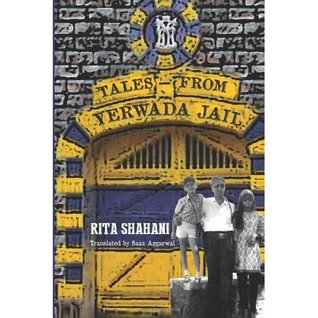

Written in 1999, Shahani drew on the bedtime stories her husband Vishnu would tell their children about his life as a freedom fighter. This book uses different voices with different perspectives to present an all-round view of the Indian freedom struggle, the RSS, the bitterness at the loss of Sindh – on 15 August 1947, Vishnu ripped up the flag in anguish – and some changes that took place after Independence. Translated into English as

Written in 1999, Shahani drew on the bedtime stories her husband Vishnu would tell their children about his life as a freedom fighter. This book uses different voices with different perspectives to present an all-round view of the Indian freedom struggle, the RSS, the bitterness at the loss of Sindh – on 15 August 1947, Vishnu ripped up the flag in anguish – and some changes that took place after Independence. Translated into English as